Reviews of The Swan-Bone Flute

Listen to real swan-bone flute music:

Use this form to get The Swan- Bone Flute Second Edition in the UK, paperback book.

(Books are not signed by the author: copies come direct from the printer to you.)

When you get your copy of The Swan-Bone Flute using this order form, you receive a beautiful bookmark specially created by Katherine Soutar – free!

I'll send your bookmark separately.

Price in the UK is £16.66 – includes postage and packing, and free bookmark.

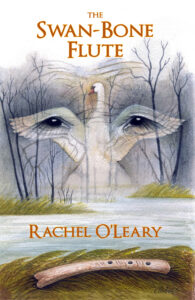

Second Edition front cover. Artwork © Katherine Soutar

Thinking how many copies to order of The Swan-Bone Flute? How many of your friends will enjoy it? Who needs a life-changing experience? Read these comments

'I loved this book. I like good historical novels, and if they have strong and smart female characters, if they consider cultural shifts toward systemic patriarchy, so much the better. But when they bring in a profound awareness of the land, its medicines, and ceremony, that is a book I can’t put down. This story is replete with insight, and characters who ask things like ‘Who would speak for the wild?’

'The women in The Swan-Bone Flute cope with change and challenge, faced with dilemmas that countless women have known, in feudalizing and colonizing societies, that continue in our own times. The transformations they go through, and the subtle teachings of the wandering bard Hilda, speak to the lives of women today, and what we are reaching back to recover.'

Max Dashu, Director of the Suppressed Histories Archive and author of Witches and Pagans, Women in European Folk Religion, 700–1100

'We all half-remember the stories of The Swan-Bone Flute. We have inherited them in our DNA. Meg, Hilda and all the others are strangely familiar; we catch sight of them with the corner of an eye or dance with them in our dreams. Reading The Swan-Bone Flute is like sleep-walking in our mothers’ memories or overhearing whispered gossip about nearly-forgotten neighbours.

The characters Rachel O’Leary has conjured are well rounded and colourful, jumping off the page and into the imagination. This is a book you will want to savour. It will enthrall and enchant you and fill you with righteous indignation. Travel with Hilda as she battles to raise the consciousness of the women who have had their ancient status and rights stripped from them and cheer for Meg as she steps into her female power.'

Maddie McMahon, Author of Why Doulas Matter and Why Mothering Matters

Live in East Anglia? Come to Ely!

Let's meet up over a cuppa. Email me to arrange where and when. You can have a bookmark too, and I'll sign your book!

You can read an extract from The Swan-Bone Flute here.

Here are some reviews of The Swan-Bone Flute from readers.

If you would like your thoughts added to this collection, please contact the author.

Reviews of

The Swan-Bone Flute

Max Dashu

Director Suppressed Histories Archives

Author of

Witches and Pagans,

Women in European Folk Religion, 700–1100

writes:

My review of The Swanbone Flute, new book by Rachel O'Leary

First published at:

Re-published here with thanks for permission

A girl leaps out of her tree perch to warn a pregnant doe that a hunter is drawing his bow against her. For this act of defending the mother deer, who should never be hunted, her uncle beats her. And so this novel drops us into the world of East Anglia in the year 598, in the wake of the Saxon invasions and enslavement of some of the British population. In this world, the old folkmoot councils are threatened by the rising power of the thanes, a hierarchy of lords under the new Saxon kings. And these lords are eroding women’s power at a rapid pace.

The spirited girl Meg is a thrall enslaved to a Saxon family. Her mother, the healer Seren, is devoted to Breejsh, a local form of the ancient Celtic goddess Brigit / Brigindo. Her power is constantly curbed by bondage and its constant work load; she has no freedom to roam the land communing with its spirits. Mother and daughter undergo daily indignities at the hands of the settler farm family who hold them in thralldom, with slaps and hard words from the women and the threat of rape from the men. The mistress forbids their religious expression and even their language. Seren hisses a warning: “Don’t let the Angles hear you speak in British; we’ll all get beaten.”

Meanwhile, the Saxon women find themselves disregarded and sidelined by the machinations of husbands and fathers. Young Ursel is in danger of being used as a chess piece by her uncle, as he jockeys to raise his own status by pleasing the powerful thane. Kedric didn’t want to look bad by not having meat to feast his lord with, and so he beat his niece. Now he wants to arrange her marriage, child as she is. And he allows the thane to requisition most of the family’s food supply to feed men building military ramparts. Old elder Edith sees all this, but will she have the power to intervene?

Into this tangle arrives Hilda the Bard, a homeless storyteller with her own harrowing story. Hilda has kept an eye out, in all her wanderings, for an apprentice capable of carrying on her cultural legacy. She is determined to awaken the women to their loss of power in the feudal patriarchy now coming into being. Hilda attempts to unite them against a backdrop of unfolding conflicts, using stories about earlier times to model self-respect and what mutual solidarity could do to change things. She teaches by indirection while dodging the ever-present threat of being thrown out on her ear. Her stories in this book follow a widespread medieval style of stories-within-a-story.

The book vividly and realistically presents the life-ways of eastern England, its landscape, the farm work, and women’s indispensible contribution to the community’s survival. The planting spells are loosely modeled on survivals of Anglo-Saxon chants, and true to their spirit. The women are shown calling on the Mere-Wife (goddess of the marshes) to help a woman in childbirth. “She protects with her tusks and blue scaly hide.” The story doesn’t shy away from the harsh reality of infant mortality, but it also highlights how wisewomen like the healer Wendreda aided women:

“Then she told me — there was a time when women came together around the time of birth, to sing the baby out, to stroke and smooth the mother’s back, to wash her with sweet herbs and dance with her, and hold her firmly. Babies can slide out with wonder in their eyes, she said, not bawling. Mothers can give birth and feel their strength. Keenbur, this is how we will help you, when your time comes.” [142]

But the author does not over-idealize the relations between women, least of all the ethnic and class divisions. Seren has to constantly hold her tongue in the face of insult: “‘slave’! The word tasted of bile and carried the crunch of breaking bone in the sound of it.” [149] But the mistress Oswynne herself admits that she was exchanged like a gift between men. Hilda draws the women out about the unspoken slights and wrongs that they suffer, and about their fears. At one point, Elder Edith recounts how a clan mother long gone stood up to the men and demanded they listen to the women: “Women get a voice.” [163] The question is, can the women restore the old ways of council — and will enslaved people have a voice in the council?

Rachel O’Leary brings her experience in herbal lore and breastfeeding counseling to the story. Her intimate knowledge of the landscape — its waterways, deer, birds and plants — is expressed with poetic eloquence. She has done her research and it shows, but never to the detriment of this engaging story about women on the cusp of christianization, and her recreation of the old festivals.

Some of the stories draw on authentic medieval precedents, such as the What Women Want tale, here presented as The Rowanberry Dress. (This kind of renovation and improvisation on old tales follows a long medieval tradition.) The author also integrates the old theme of women as “peace-weavers” with her study of conflict resolution and the revival of council practices of respect and dialogue:

“We get everyone together first for a blessing, so they know it’s important. Everyone gets heard. We listen together, root to root. We ask questions to burrow underneath the words and get to the hurt places, and down further to find the needs. Chew all that over, without shouting or name-calling. Then we start putting together ideas for a path out of the swamp — not a punishment, but a way we can all live together again.”

Many cultural gems are embedded in the text, like the elders withdrawing “to deem our Doom.” This is a reminder of an extremely ancient Indo-European concept, which originally meant “law, judgment, decree, fate,” not “downfall” as in modern English. The word doom is related to Themis, the archaic Greek goddess of divine law and justice, she “of good counsel.” But that is just me geeking out; you don’t need to know this stuff to enjoy the novel.

The cover painting by Katherine Soutar could not be more perfect. It captures the essence of the book: the wise eyes of the old storyteller, her unity with the swan and the fen spirits of heathen England.

I highly recommend this book. It is not a fantasy, but a clear-eyed recreation of a lost cultural world, which does not attempt to gloss over oppression, but never loses sight of what is precious in that heathen heritage. The book is replete with insight, and characters who ask things like, “Who will speak for the wild?”

I can’t wait to read the next instalment in The Storytellers Trilogy. The book is published by Bog Oak Press (2019) and is available through the usual outlets.

Maddie McMahon

Author of

Why Doulas Matter

and

Why Mothering Matters

writes:

We all half-remember the stories of The Swan-Bone Flute. We have inherited them in our DNA. Meg, Hilda and all the others are strangely familiar; we catch sight of them with the corner of an eye or dance with them in our dreams. Reading The Swan-Bone Flute is like sleep-walking in our mothers’ memories or overhearing whispered gossip about nearly-forgotten neighbours.

The characters Rachel O’Leary has conjured are well rounded and colourful, jumping off the page and into the imagination. This is a book you will want to savour. It will enthrall and enchant you and fill you with righteous indignation. Travel with Hilda as she battles to raise the consciousness of the women who have had their ancient status and rights stripped from them and cheer for Meg as she steps into her female power.

Avril Dawson

writes:

The Swan-Bone Flute is packed with wisdom, beauty, thoughtfulness and understanding, love, knowledge, intuition, all wrapped up in the most accomplished storytelling.

Cath Little, Storyteller

Author of

Glamorgan Folk Tales for Children

Review of The Swan-Bone Flute by Cath Little

Review first published in

Facts & Fiction No.111 November 2019, re-published here with permission

Cath Little writes:

“You can choose tales that keep your nose in the dirt – or look around for talk that lifts you. Then it’s up to you: will you stand up for each other, and yourselves, or go on letting things happen?”

These are the words of Hilda, the travelling storyteller, who has arrived at a settlement on the edge of the English Fens. It is 598 C.E., a time of great change and uncertainty. Hilda hopes that the stories she shares will help bring the community together. And Rachel O’Leary gives Hilda some wonderful stories to retell – The Dead Moon, What Women Want and The Laidly Worm among others, and, just as importantly, she shows why and how Hilda shares these stories to build empathy and understanding between her listeners.

The Swan-Bone Flute is historical fiction, well researched, with an added dash of fantasy. It’s a book which celebrates mothering and women’s lived experiences. I enjoyed the evocation of our ancestor’s lives but I recognized too that the mothers’ challenges of nurturing, feeding, caring, healing and teaching still remain the same. One description of a young mother cooking a family meal with a toddler underfoot, a baby at her breast and a hundred other demands on her time was familiar to me from life. I was surprised to realise how rarely I’ve seen this shown in a book.

This book is a deeply ecological book. A teenage girl disrupts the deer hunt when a hind is endangered, reminding her people that “when hunters take care of the deer herds, they flourish, and so does the whole forest.” When Hilda finds a community divided and facing the threat of change she helps them re-instate the old folk way of The Moot. At The Moot everyone sits down together, listens to one another and together makes a decision on what needs to be done.

I did find The Swan-Bone Flute a bit over-long and some of the details and side stories made me occasionally lose my way. But Rachel has a lot to say. This book gave me a temporary escape into another world as well as a chance to reflect on the big questions that face us. The Swan-Bone Flute reminds us of the interconnectedness of things, the value of community and the importance of telling stories that “lift you.”

Ellen Mateer

writes:

Wonderful book to read in long stretches during a pandemic.

Nell Buckley

writes:

... beautiful believable characters with whom one feels a great affinity. I felt really close to all my fellow womankind after reading it.

What's your favourite magazine or website? If readers write reviews of The Swan-Bone Flute, more people will be able to find the book and enjoy it.

K. Ann Hambridge in Canada

writes:

I am re-reading The Swan-Bone Flute. The first time was rapid which gave me a wonderful overview and whetted my appetite.

Now I’m taking the time to savour the depth of characters. While I know the main impact is empowering women and drawing similarities with 2020s morals (or lack of), understanding backgrounds and motivation brings a very rich experience.

Seren is fascinating. What an inspiring role model! ...

In my first read I missed the humour and irony of many situations. Love it all.

Read Chapter 1 of The Swan-Bone Flute here ...